True Crime Meets Academia—Dr. Charles Woods Shares His Research

Part 4 of the Spooky Stories Series

Content Warning: Although not described in detail, this article does mention topics of murder and sexual assault that may be triggering to some.

For October, we have been exploring scary stories at A&M-Commerce, from children's horror stories to legends of ghosts on campus and myths about the Salem Witch Trials. But not all are confined to October. Dr. Charles Woods, a composition and rhetoric professor in the Department of Literature and Languages at Texas A&M University-Commerce, knows this all too well through his research, which often ventures into true crime.

Woods focuses his work and research on the topic of digital privacy, often discussing cases of police using familial DNA sites as a surveillance tool. He and some colleagues formed the Digital Rhetorical Privacy Collective (DRPC), an online community of students and scholars working together towards better understanding privacy policies and how they impact consumers.

Woods also received a grant to start a “Privacy Lab” on the A&M-Commerce campus, which will be dedicated to his and his colleagues' DRPC work. Woods often marries the topic of digital privacy with his passion for podcasting, frequently discussing the topic often on his award-winning podcast, “The Big Rhetorical Podcast.”

The professor also incorporates podcasts and digital privacy in the classes he teaches. For example, in his “Writing with Digital Media” class, he encourages students to create their own podcasts and audio projects.

Woods' digital privacy research was largely inspired by the true crime case of the Golden State Killer, a serial killer in California. To understand the case and the impact it had on Woods' academic work, we must start by journeying 1,400 miles and 50 years back in time to California in the mid-70s.

The Case That Inspired It All

Between 1974 and 1986, a serial killer was on the loose, committing 13 murders, 51 rapes, and more than 100 burglaries across the Golden State.

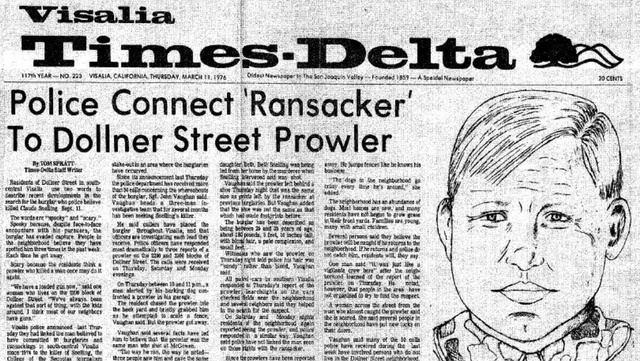

Authorities initially believed multiple people committed these crimes because the incidents were spread so far across the state, and law enforcement lacked a common database or the ability to easily share information among different counties. In Sacramento, the police and media dubbed their unknown criminal “The East Area Rapist.” In Visalia, he was dubbed “The Visalia Ransacker.” And in the Santa Barbara and Orange County area, he was known as “The Original Night Stalker.”

For decades, these murders, rapes, and burglaries went unsolved. Then, in 1986, they suddenly stopped. Despite police efforts, all the cases went cold.

In 2001, DNA evidence revealed a startling revelation: the East Area Rapist and the Original Nightstalker were the same. Police then began sharing information—comparing notes, cases, and suspects—but everything still led to dead ends.

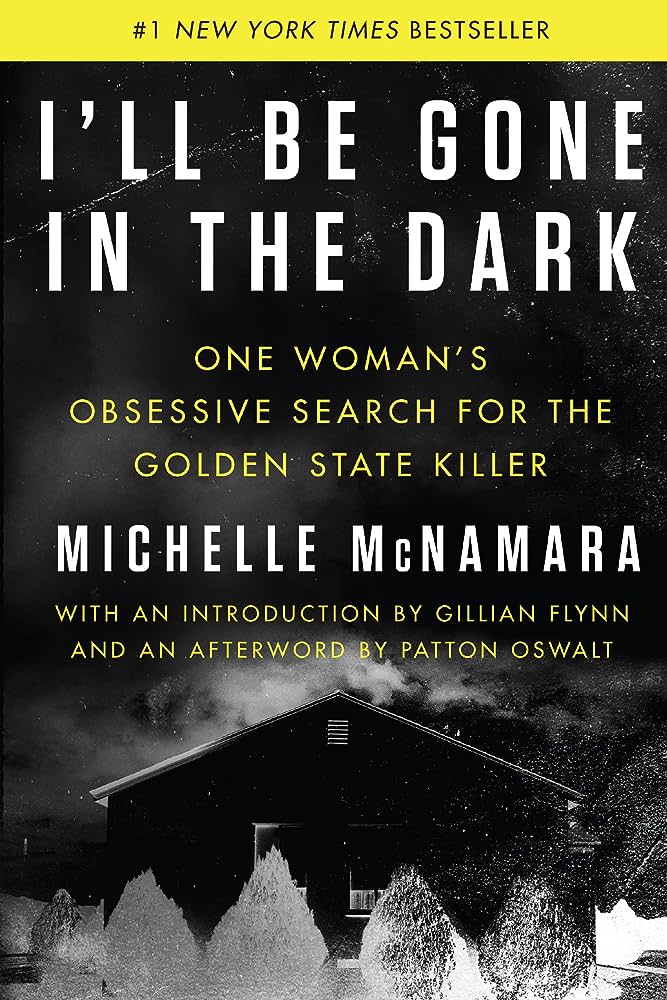

Five years later, a crime journalist named Michelle McNamara began studying and writing about the East Area Rapist, the Visalia Ransacker and the Original Night Stalker. She suggested that due to the shared “modus operandi” (MO), perhaps the Visalia Ransacker was the same person as the East Area Rapist/Original Nightstalker. Investigators tested the DNA, which proved her hunch to be right. McNamara gave the unknown suspect a new moniker: The Golden State Killer (GSK).

Building on the work she did with her online community, McNamara began writing a book about the GSK, hoping to see him brought to justice someday. Unfortunately, she passed away in 2016, leaving the book unfinished. Her husband, actor Patton Oswalt, and close friend, Billy Jensen, completed and published the book in February of 2018 in her honor.

Then, as if McNamara was somehow working from the grave, in April of 2018, there was breaking news:

Forty-four years after his crime spree, investigators revealed the Golden State Killer's identity as 73-year-old Joseph James DeAngelo.

The police caught DeAngelo with a new and innovative investigation method utilizing familial DNA through a site called GEDmatch. Like 23 and Me or Ancestry.com, users submit their DNA samples to GEDmatch to find ancestors and relatives.

“Police used the output to match a relative of the Golden State Killer, DeAngelo, and built a family tree,” Woods explained. “So, they had this big family tree and found some people on the tree who fit the profile, which led them to DeAngelo.”

Once the police flagged DeAngelo, they went through his discarded trash to collect a DNA sample and successfully matched it to the sample they had in evidence.

Woods excitedly exclaimed, “And BOOM! We have the most notorious serial rapist and sexual offender in California’s history. We have identified the person!”

Case closed: the good guys were brilliant, and the bad guy was caught. End of story, right? Woods suggested otherwise.

“So,” he said, “all that occurred right when I was working on my dissertation. And I was like, ‘How do I not write about this? I have to write about this.”

Charles Woods's Research

Woods was already interested in digital privacy before police caught DeAngelo, but when the GSK case broke, it felt like the stars aligned. A topic that once might have seemed niche was suddenly incredibly relevant, and not many people in academia were talking about it. He knew he had two unique ideas to contribute to the larger conversation about the case and the way it was solved.

1. Digital Privacy

First, Woods questioned the ethics of testing DNA samples without owner consent. Consent, he explained, is where the lines begin to blur, and things turn to grey.

“The Sacramento Country Sherriff's Department violated the GEDmatch's privacy policy for gaining consent to submit genetic data to their website because it wasn't their personal genetic material they uploaded. The assumption on sites like GEDmatch it that users upload their own DNA, not someone else's,” Woods said.

Additionally, when DeAngelo's family members uploaded their DNA profiles to GEDMatch, they believed it was for a private company helping them learn about their genetic history. They never consented to the use of their DNA as evidence in an investigation.

At the time of the GSK investigation, this police tactic of using familial matches to identify a suspect was brand new; therefore, there were no laws regulating governmental or law enforcement agencies’ usage of the sites. Although some individual states have created laws addressing the issue, no federal law exists. And this, Woods suggests, is problematic. He believes that users should be able to opt in or opt out of using their DNA for police investigations.

“Now, that doesn't stop rogue police officers from potentially using the technology on their own,” Woods clarified, “but certainly allowing users to opt in or out is the best practice.”

2. Digital Writing and Communities

In his research, Woods also connected the work of digital privacy to the power of digital communities. He was inspired by McNamara's work and the ways she worked with a community of researchers through online tools like forums, message boards, and emails.

“True crime fans, retired law enforcement officers, general researchers—all types of people interested in the case all worked together to help solve it. That's grassroots activism,” he affirmed.

When Woods witnessed the power of digital communities in the GSK case, he considered the evolution of digital writing, specifically podcasts and their ability to spread information and involve listeners. This, combined with digital mediums like message boards and online forums, allows true crime fans to participate actively in cases.

“It's produced a type of activism and facilitates change in the community regarding justice and police reform,” he explained.

Woods also referenced the podcast “Serial” as another true crime podcast that inspired him to think about digital communities. The podcast highlights the story of Adnan Syed, a young man convicted of murdering his girlfriend in 2000. Host Sarah Koenig began probing the case, suggesting Syed was wrongfully imprisoned. When “Serial” became popular, many listeners began advocating for Syed's release. Because of the public outcry and pressure, in 2023, a judge vacated Syed’s conviction.

Woods said “Serial” was incredibly significant in the true-crime and podcasting community.

“That podcast bred activism,” he explained. “It moved from digital activism to making change in the world.”

Tying Things Together

Inspired by the GSK case, the role DNA sites played, and McNamara's work, Woods went on to write his dissertation, “Interrogating Digital Rhetorical Privacy on Direct-To-Consumer Genetic Websites.” In it, he addressed the ethical concerns of police using sites like 23-and-Me or Ancestory.com as tools for surveillance. In his conclusion, he suggested that the best way to combat digital privacy and surveillance issues is to utilize digital technologies to build community, share resources, and work together better to understand digital privacy and work towards potential change. And of course, in his dissertation, he tells the story of the GSK and the role it played in his work.

After successfully defending his dissertation, Woods has continued his work in true crime, digital privacy, and podcasting with projects like the DRPC, “The Big Rhetorical Podcast,” and by teaching his own classes. In 2020, he and a colleague published an article titled “Negotiating Ethics of Participatory Investigation in True Crime Podcasts” on utilizing true-crime podcasts ethically in the classroom.

He sees true crime and podcasts as tools to empower students, often incorporating them into his classes and assignments, and encourages other professors to do the same.

“I would encourage faculty and staff to think about how they can integrate multimodal assignments or texts into their classes and even bring in true crime,” he said.

Woods hopes that instructors recognize that podcasting is one of the most innovative fields, both inside and outside academia, and would consider incorporating podcasts and podcast projects in their classes.

Woods also encouraged true crime consumers to get involved.

“Consider our local context and the rich resources around you,” he recommended. “Make your own true crime project! See what has been done already because there's stuff people are doing. Get involved!”

Whether making a true crime podcast themselves or advocating for things like unjust prison sentences or digital privacy, Woods sees the genre of true crime as more than just something interesting or entertaining. To him, it's a pathway to knowledge, activism, and a potential tool for changing the college classroom and the world.

If true crime, digital privacy, or podcasting interests you, check out the Composition and Rhetoric program for graduate students at A&M-Commerce, where you can take classes with Dr. Charles Woods and explore topics that interest you creatively and innovatively!